|

The Clavis or 'Key' of

|

|

The Clavis or 'Key' of Jacob Boehme, the seventeenth-century German theosopher, is a condensed version of the principal points of his mystical philosophy. Boehme, an unschooled shoemaker, experienced while young an intense vision of the spiritual world - a vision of the origin of the universe, the struggle of polarities in creation, and the role of Sophia or Divine Wisdom in the world. This vision inspired his writings and left him with a deep sense of the spiritual all his life. In trying to find a language to communicate his mystical perceptions, he turned to alchemical ideas and Hermetic imagery. The main period of his writings, 1612-1624, coincided with the Rosicrucian publications, and while no definite historical link can be established, Boehme certainly worked within the spirit of the Rosicrucian movement. Reviews and Comments: "An excellent starting point for delving into the works of this remarkable author, so central for the Christian theosophic and mystical traditions." - Arthur Versluis, author of Wisdom's Children and Theosophia

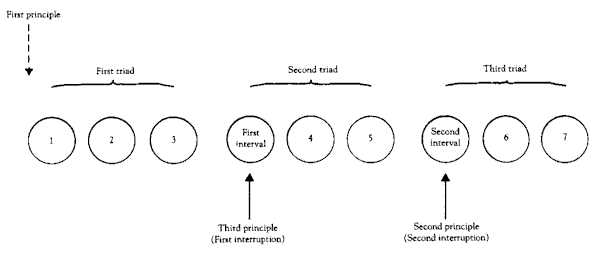

Following is a brief, modern interpretation of the "Threefold Structure" and the "Sevenfold Self-Organization of Reality". It is taken from the book: "Science, Meaning, and Evolution", written by Basarab Nicolescu, a physicist working with "Quantum Physics". Buy your INEXPENSIVE books at one of these sites: Amazon, Alibris, Abebooks. Download a FREE .pdf [ Here ]. To skip this, and go directly to "The Key", CLICK Here. You may also download an eBook containing the full "Collected Works of Jacob Boehme by clicking [ Here ]. A: THE THREEFOLD STRUCTURE In the cosmology of Boehme, reality is structured in three parts, determined by the action of three principles: "Now thus the eternal light, and the virtue of the light, or the heavenly paradise, moveth in the eternal darkness; and the darkness cannot comprehend the light; for they are two several Principles; and the darkness longeth after the light, because that the spirit beholdeth itself therein, and because the divine virtue is manifested in it. But though it hath not comprehended the divine virtue and light, yet it hath continually with great lust lifted up itself towards it, till it hath kindled the root of the fire in itself, from the beams of the light of God; and there arose the third Principle: And it hath its original out of the first Principle, out of the dark matrix, by the speculating of the virtue [or power] of God." These three principles are independent, but at the same time they all three interact at once: they engender each other, while each remaining distinct. The dynamic of their interaction is a dynamic of contradiction: one could speak of a negative force corresponding to the darkness, a positive force corresponding to the light, and a reconciling force corresponding to what Boehme called "extra-generation." It is a question of a contradiction among three poles, of three polarities radically opposed but nevertheless linked, in the sense that none of the three can exist without the other two. The three principles have a virtual quality, for they exist outside our space-time continuum. As a result they are, in themselves, invisible, untouchable, immeasurable: "We understand, then, that the divine Essence in threefoldness in the * unground dwells in itself, but generates to itself a ground within itself . . . though this is not to be understood as to being, but as to a threefold spirit, where each is the cause of the birth of the other. And this threefold spirit is not measurable, divisible or fathomable; for there is no place found for it, and it is at the same time the unground of eternity, which gives birth to itself within itself in a ground." The foundation of the Trinity is "subject to no locality, nor limit [number], nor place. It hath no place of its rest. * TRANSLATOR'S NOTE: Boehme's term "unground" - Ungrund in German and sans-fond in French - refers to this mysterious "bottomless state" which at the same time serves as the base or foundation or ground where the Trinity dwells. It is important to stress that it is exactly this process of contradiction which allows manifestation. The hidden God (Deus absconditus) is not pure transcendence. Through the two other poles of this ternary contradiction, he can show himself, he can manifest, he can respond to the wish to understand himself. Thus the three forces corresponding to the three principles will be present in every phenomenon of reality: "And no place or position can be conceived or found where the spirit of the tri-unity is not present, and in every being; but hidden to the being, dwelling in itself, as an essence that at once fills all and yet dwells not in being, but itself has a being in itself. . . ." God hidden thus becomes God manifest (Deus revelatus). In this context, it is extremely interesting to remark the role that Boehme attributes to our own world. The three principles engender three different worlds which moreover are overlapping - the world of fire, the world of light, and the exterior world: "And we are thus to understand a threefold Being, or three worlds in one another. The first is the fire-world, which takes its rise from the centrum naturae. . . . And the second is the light-world which dwells in freedom in the unground, out of Nature, but proceeds from the fire-world. . . . It dwells in fire, and the fire apprehends it not. And this is the middle world. . . . The third world is the outer, in which we dwell by the outer body with the external works and beings. It was created from the dark world and also from the light-world. . . . The exterior world, our world, appears as if it were a world of true reconciliation. It is not the world of the Fall, the world of man's guilt, of his downfall into matter. As Pierre Deghaye remarks pertinently, our world is a world of reparation: "The body of Lucifer is set on fire and it is destroyed. But this body was the universe before ours. It is the result of this catastrophe and in order to repair it that our world was created. Our world is the third principle." All the grandeur of our world resides in the incarnation of these three principles. First of all, the threefold structure of reality is inscribed in man himself. Man is the actualization of this threefold structure:" . . . so also in like manner is every mass or seed of the Ternary or Trinity in every man," Boehme tells us. Human nature, merging the three principles, "understands therefore, at least potentially, the totality of divine manifestation." What man makes of this human nature is, of course, a whole other story. In our modern world, man has forgotten that he is potentially the incarnation of three principles. The very words "three principles," not to mention their meaning, seem to us strange and absurd. We are, evidently, far from the work of spiritual alchemy, based on the balance of our own threefoldness, a work to which Boehme invites us, and which alone could give this world a real meaning. Otherwise our world is dead, absurd, accidental. What interests us here in the first place is the manifestation of the threefold structure of all the phenomena of Nature. Of course, one must not confuse "nature" and "threefoldness": "Nature and the Ternary are not one and the same; they are distinct, though the Ternary dwelleth in nature, but unapprehended, and yet is an eternal band. •""' But in every phenomenon of Nature threefoldness perpetually appears. The Trinity, this "triumphing, springing, moveable being" is the "eternal mother of nature." Even if the three principles are enclosed "in no time nor place," they manifest themselves nonetheless in space and time. The third principle has a crucial role in this manifestation; it is what "contains the fiat, the creative word of God."' Everything becomes a trace, a sign of threefoldness: man, the planets, the stars, the elements. The alliance between nature and threefoldness is eternal, but man has the choice between discovering and living this alliance or forgetting, ignoring, and therefore disrupting it. One thus understands the deep relationship between the thought of Boehme and that of Galileo, even if it is implicit and surprising, for their languages are very different. When Galileo points out the importance of experimental observation, separating experiment from sentient evidence (that furnished by the sense organs), he is very close to Boehme, for whom nature is a manifestation of divinity, and insofar as it is a manifestation, is measurable and observable. Both of them, like Kepler as well, are haunted by the idea of laws and invariance. The idea that it must be possible to reproduce phenomena, fundamental for the methodology of modern science, comes in here. The "new science" does not concern itself with singular phenomena but with those which are repeatable and which submit to a mathematic formalization. Galileo, like Boehme, did not identify human reason with divine reason. Maurice Clavelin points out that the position of Galileo "is lucid: created by an infinite being, the world is on the scale of his reason, not human reason, which understands it only within the limitations of its capacities, that is, through what it has in common with divine reason; mathematics is precisely in this position." The difference between the two approaches, that of Galileo and that of Boehme, is also of paramount importance. For Galileo, every divine "cause" must be excluded in the formulation of a scientific theory, while for Boehme the comprehension of reality must take into account the participation of the divine in the processes of our world. The mathematics of Galileo is strictly quantitative, while that of Boehme is qualitative, of a symbolic order. Since Nature has a double nature, so also does modern science. Modern science has been developing itself for several centuries on the path traced by Galileo instead of the far more obscure and complex one implicit in the works of Boehme. Galileo's success was staggering, as much on the level of experiment as on that of theory. His technological applications, demonstrating the mastery of man over nature, seemed to show the indisputable accuracy of this approach. Founded on binary logic, that of "Yes" or "No," modern science reached its peak in the nineteenth century, in a scientistic ideology proclaiming that science alone, human reason alone, had the exclusive right-of-way to truth and reality (though the position of Galileo was, as we have seen, quite different: non-positivist and nonscientistic). The scientistic ideology began to fall apart at the birth of quantum physics, with the discovery of a level of reality that clearly differs from our own; this, in order to be understood, seemed to demand a threefold logic, that of the included middle.' Moreover, an unexpected encounter seems to be coming about just now between modern physics and traditional symbolic thought. I have analyzed these aspects at length in my book, Nous, la particule et le monde and I ask the reader to refer to that in order to avoid too many annoying repetitions here. In any case, the resurgence of * meaning in modern physics,' is the sign of the double nature of modern science: by excluding meaning from its domain, modern science rediscovered it, by means of its own internal dynamic, on its own road. * AUTHOR'S NOTE: The French word "le sens" ("meaning") has to be understood here in a very general philosophical, metaphysical, and experiential way. At its most basic, "meaning" refers to the fact that many processes which initially seem chaotic or disordered may, if properly studied, be seen to have a significance or direction that reveals the presence of order. In this sense, "meaning" and "laws" are intimately correlated. In a deeper way, and especially in Boehme's writings, "meaning" refers to the unitive interaction between different levels of reality, in a harmonious, evolutionary movement. More precisely, "meaning" is the contradictory encounter between presence and absence, things sacred and profane. In our physical universe, since consciousness is thought to be present only on the planet Earth, the individual and mankind have a cosmic role: to simultaneously discover and produce "meaning." Through his body, senses, and sensations, man becomes the cosmic instrument of "meaning." Experiences and experiments are two facets of discovering "meaning." This is why the study of the universe and the study of man are complementary Will there then be a return to the ideas of Boehme? It would be hazardous to formulate any such affirmation. But what seems certain to me is the current necessity for formulating a new Philosophy of Nature. Understanding Boehme's work thus has a real immediacy in this context today. A comparison between his idea of threefoldness and that of modern thinkers such as Stéphane Lupasco or Charles Sanders Peirce would thus be highly instructive but it goes beyond the framework of this book. It is sufficient to say here that astonishing correspondences can be established between the threefoldness of Boehme, the triad of Lupasco (actualization, potentialization, and the T-state, the "included middle"), and the triad of Peirce ("firstness, secondness, and thirdness," as he calls them). Boehme speaks of "three worlds," Lupasco of "three matters," and Peirce of "three universes." Indeed, the different triads evoked are far from identical. The source of threefold thinking in Boehme, Lupasco, and Peirce is equally different: an inner experience on Boehme's part, quantum physics for Lupasco, and mathematical graph theory for Peirce. But one and the same law seems to manifest itself, under different facets, in all who think in threes, and it is that which produces the threefold structure of reality, in all its manifestations. We are left to understand how a virtual structure can set in motion the different processes of reality. B: THE SEVENFOLD SELF-ORGANIZATION OF REALITY If threefoldness concerns the inner dynamics of all systems, sevenfoldness is, according to Boehme, the basis, in its inexhaustible richness, for the manifestation of all processes. Sevenfoldness functions in continual interaction with threefoldness: it is precisely this interaction which furnishes the key to a full comprehension of reality, at least in the view which Boehme proposes to us. First of all, why choose the number seven? In the beginning it is difficult to understand why any number, even on the level of symbolic thought, should be more important than any other, in an absolute and definitive way. Why, for example, should the number 7 exclude all interest in the numbers 4 or 9 or 137 or 1010? Of course, the mystic, theological, or symbolic value of the number seven is well known. Alexander Koyré's thesis provides an almost exhaustive list of the different meanings of the number seven which could be applied, more or less, to Boehme's sevenfoldness: the seven lights and the seven angels of the Apocalypse, the seven lower sephiroth of the Kabbalah, the seven alchemical processes, the seven planets (a favorite hypothesis of Koyre), and so forth. Personally, I think one can demonstrate that all these are false trails. Correspondences between the different meanings of sevenfoldness could certainly be found, but I believe, for reasons I will explain later, that Boehme had no exterior source of inspiration for his concept of sevenfoldness other than his own vision. Moreover, sevenfoldness asserts itself in the philosophy of Boehme as a relentlessly logical consequence (following symbolic logic, of course) of one of the keystones of his thinking: that the basis of all manifestation must be in perpetual interaction with threefoldness. It is amusing to ascertain that it is precisely this interaction which has plunged many of Boehme's commentators, as Koyré told us, "into the most cruel difficulty." Koyré himself speaks of the "unhappy diagram of seven spirits that Boehme maintains against all odds." He also says: "it would not be easy to classify these seven powers into three principles and to coordinate them to the three persons of the Trinity, but Boehme was never able to abandon this sevenfold framework." Very fortunately, I would be tempted to add. I do not pretend to offer a unique and definitive solution to this enigma, but I believe I can give a perfectly coherent reading of it, on the level of symbolic logic, from Boehme's own texts alone. For Boehme, "God is the God of order . . . Now as there are in him chiefly seven qualities, whereby the whole divine being is driven on, and sheweth itself infinitely in these seven qualities, and yet these seven qualities are the chief or prime in the infiniteness, whereby the divine birth or geniture stands eternally in its order unchangeably." Every process of reality thus will be ruled by seven * qualities, seven spirit-sources, seven stages, seven patterns. * AUTHOR'S NOTE: Since "quality" is a key word in the cosmology of Boehme, it cannot be understood through any dictionary-type definition. Boehme's seven qualities are the intermediate, active, informational energies which give shape to all the various levels of reality. It is important to stress that the seven qualities are each generated by a particular interaction of the Three Principles. This explains a paradoxical and crucial property of these seven qualities: they are always the same, even though they adapt to the given level of materiality on which they are acting. Different levels of materiality do not imply different levels of the seven qualities. It is precisely this property of their always remaining the same which allows the possibility of cosmic unity, through the interaction of all levels of reality. Evolution itself - cosmic evolution, evolution of the individual, or evolution of mankind- therefore becomes possible. The names which Boehme attributes to these seven qualities are poetic and highly evocative, but they can appear somewhat naive and to the modern reader: Sourness, Sweetness, Bitterness, Heat, Love, Tone or Sound, and Body. But what interests us here are not the names, but the meanings which Boehme attributes to them in the context of sevenfoldness. Restricted by everyday language, Boehme first adopts a linear, chronological description of how these seven qualities are linked in the sevenfold cycle, but understanding them comes through a simultaneous consideration of their actions. The spirit-sources all give birth to each other, yet each remains distinct. Again, only a logic of contradictions gives us access to the meaning of Boehme's sevenfoldness. To begin with, let us proceed, like Boehme, by stages. The three first qualities proceed from the first principle. The God of the first principle is, for us, a God who is impenetrable and unknowable. He appears to us like a God of darkness, a God of terrifying night, because he is unfathomable. One cannot even truly call him God. An intense and bitter struggle takes place among the first three qualities to permit this God of darkness to know himself in his potentiality. Why does this struggle begin among three qualities and not four or six? According to Boehme, the God of darkness, once started on the road to self-knowledge, must submit to his own threefold nature.

The merciless struggle among the first three qualities produces a true "wheel of anguish." The world of the first triad of sevenfoldness is a "dark valley," a virtual hell. Boehme speaks of "an anxious horrible quaking, a trembling, and a sharp, opposite, contentious generating." Something must happen to allow the "childbirth," the passage to life, to manifestation. It is precisely at this point, when the wheel of anguish turns frantically on itself, in a chaotic, infernal whirlwind, that a principle of discontinuity must be manifested, to open the way for true evolutionary movement. This principle of discontinuity is none other than the third principle, which appears as the fiat of manifestation, the creative word of God. Boehme calls this discontinuity a "flash": "Behold, without the flash all the seven spirits were a dark valley. " The insane movement of the wheel of anguish stops in order to transform itself into harmonious movement. It is now that life can be born, that God is born. The fiat of manifestation, generated by the third principle, becomes an integral part (although merely virtual, because it corresponds to an invisible interruption on the level of manifestation) of the second triad of the sevenfold cycle, which equally includes the fourth and fifth qualities: "Now these four spirits move themselves in the flash, for all the four become living therein, and so now the power of these four riseth up in the flash, as if the life did rise up, and the power which is risen up in the flash is the love, which is the fifth spirit. That power moveth so very pleasantly and amiably in the flash, as if a dead spirit did become living, and was suddenly in a moment set into great clarity or brightness." The fact that the fourth and the fifth qualities are intimately linked to the lightning flash, and therefore to the third principle, is thus clearly affirmed. The cold fire of the first triad thus transforms itself into a hot fire from which light can burst forth: "The fourth property thus plays the role of a turntable or pivot of transmutation for the whole system, Jean-Francois Marquet has written. I would be tempted to say rather that the turntable is located in the interval between the third and the fourth quality, for it is there that the action of the fiat of life, of manifestation, takes place. "Birth" does not mean a complete manifestation of the light. With the second triad, God is born, he becomes conscious of himself, but he does not yet manifest himself fully. A second principle of discontinuity must intervene so that the evolutionary movement can continue. The fiat of affirmation, of the light fully revealed, the heavenly fiat is necessarily the action of the second principle. "The second fiat is found at the fifth degree," Pierre Deghaye correctly affirms. More precisely, it is found in the interval between the fifth and the sixth quality.

The intervention of the second principle generates a new triad of manifestation ("triad, " for each principle must submit itself to its own threefold structure). This next triad is composed of three elements: one virtual element (the interruption generated by the second principle) and two qualities: Tone or Sound, and Body. The sixth quality is that of heavenly joy, like a joyful sound which runs through the whole manifestation: "Now the sixth generating in God is when the spirits, in their birth or geniture, thus taste one of another. . . . whereby and wherein the rising joy generateth itself, from whence the tone or tune existeth. For from the touching and moving the living spirit generateth itself, and that same spirit presseth through all births or generatings, very inconceivably and incomprehensibly to the birth or geniture, and is a very richly joyful, pleasant, lovely sharpness, like melodious, sweet music. And now when the birth generateth, then it conceiveth or apprehendeth the light, and speaketh or inspireth the light again into the birth or geniture through the moving spirit." It is at the level of the sixth quality that Boehme placed language, discernment, and beauty. As for the seventh quality, it corresponds to full manifestation, to the "body" of God, which is none other than nature itself: "Now the seventh form, or the seventh spirit in the divine power, is nature, or the issue or exit from the other six. . . . [This seventh spirit] is the body of all the spirits, wherein they generate themselves as in a body: Also out of this spirit all figures, shapes and forms are imaged or fashioned." The seventh spirit "encompasseth the other six, and generateth them again: for the corporeal and natural being consisteth in the seventh." The loop is thus closed: the seventh quality rejoins the first, but on another level, that of manifestation. The line changes into a circle: paradoxically, in the philosophy of Jacob Boehme, the Son gives birth to the Father. I confess I do not understand the perplexity of Boehme's interpreters regarding the interaction between threefoldness and sevenfoldness, but the interpretation that I propose seems to me coherent, rational, and completely conforming to Boehme's texts. The cycle of manifestation ought to demonstrate the full power of threefoldness. This full power obtains when each of the three principles manifests its own threefold structure, a structure which results from the perpetual interaction between each principle and the other two principles. If each principle does not have a threefold structure, the interaction between the three principles will be mutilated or annihilated. As a result, the cycle of manifestation must include nine elements (3 x 3 = 9). But two of the elements are virtual, invisible - they correspond to two interruptions. Therefore on the visible, natural level, the manifestation cycle would have to be a sevenfold structure (9 - 2 = 7). Taken in its entirety (including therefore the two intervals where the interruptions take place that are produced by the action of the second and third principles), this cycle has a ninefold structure. One sees therefore the fundamental importance that Boehme accorded to the number nine, associating it with what he called the Tincture: "Boehme saw the temporal Universe as permeated by an immense current of life (Tincture), which, born of the Principium or Centrum (Separator) of Divinity, discharges itself upon the world, penetrates it, incarnates itself in it, and vivifying it, brings it back to God. . . The Tincture, which is the number nine, is the pure element, the divine element." Two supplementary remarks need to be mentioned for the clarification of certain aspects of the cycle of manifestation. First, we have spoken of two interruptions, of two fiats, linked to the second and third principles. Why not speak of a third interruption, linked to the first principle? Certainly "in every will the flash standeth again to [make an] opening," as Boehme has written. But, the God of the first principle is completely ungraspable by himself. To speak of a fiat bound to his will would be pure verbiage. On the other hand, this God makes himself concrete in the first triad of the sevenfold cycle. Secondly, the inversion between the action of the third principle and that of the second principle in the course of the sevenfold cycle seems very significant to me: again, the third principle, that which rules our own world, acts as a reconciling force between the first and the second. It also might be instructive to make a comparative study between the cosmology of Boehme and that of G. I. Gurdjieff (1877-1949). As with Boehme, the fundamental laws of the universe are, in the cosmology of Gurdjieff, a Law of Three and a Law of Seven, and their interaction is expressed as a Law of Nine. The threefoldness, sevenfoldness, and ninefoldness of Gurdjieff are not, indeed, the same as those of Boehme; but their comparative study could reveal interesting sidelights. We cannot attempt such a study here. But it is surprising to remark that not one of the numerous analysts of Gurdjieff's ideas speaks of the striking analogy between his laws and those of Boehme. Even his most informed biographer, James Webb, cites Boehme only casually. Boehme's sevenfold structure penetrates all levels of reality. The birth of God is repeated endlessly throughout all these levels, in "signatures" or "traces." He writes: "The seven spirits of God, in the circumference and space, contain or comprehend heaven and this world; also the wide breadth and depth without and beyond the heavens, even above and beneath the world, and in the world. . . . They contain also all the creatures both in heaven and in this world. . . Out of and from the same body of the seven spirits of God are all things made and produced, all angels, all devils, the heaven, the earth, the stars, the elements, men, beasts, fowls, fishes; all worms, wood, trees, also stones, herbs and grass, and all whatsoever is." At a certain level of reality, the sevenfold cycle can develop fully, can stop, or can even involve; the different systems belong to a level of reality that enjoys the freedom of self-organization. The divine Nature and its evolution is predetermined insofar as potentiality is concerned. But the interruption characterizing the sevenfold cycle introduces an element of indeterminacy, of liberty, of choice. As Koyré remarks: "The lightning flash is that of freedom introducing itself into Nature, which is the opposite of freedom." In Boehme's universe, determinism and indeterminacy, constraint and freedom coexist contradictorily. Is not the God of darkness, the magical source of all reality, in himself, the Great Indeterminacy? But his "hunger and desire is after substance," and he is obliged to accept a certain determinism, a certain "contraction." As Deghaye points out, "In the Kabbalah of Isaac Luria, there is a similar phenomenon: at the origin of all worlds, the Infinite contracts itself and thus begins the true drama, in the bosom of Divinity." It is on this "divine tragedy" that the greatness of our own world is founded: that of the full evolution of man. The self-knowledge of God thus rejoins the self-knowledge of man.

THE PREFACE TO THE READER |

|

Of the Third Principle, viz. The Visible World;

whence that proceeded; and what the Creator is.

133. This visible world is sprung from the spiritual world before mentioned,

viz. from the outflown divine power and virtue; and it is a * subject or object resembling the spiritual world: the spiritual

world is the inward ground of the visible world; the visible subsisteth in the

spiritual.

* "subject or object" (Gegenwurf); see *, p. 8.

134. The visible world is only an effluence of the seven properties, for it

proceeded out of the six working properties; but in the seventh (that is, in

paradise) it is in rest: and that is the eternal Sabbath of rest, wherein the

divine power and virtue resteth.

135. Moses saith, God created heaven and earth, and all creatures, in six

days, and rested on the seventh day, and also commanded [1] it to be kept for a

rest.

[1] or to rest on it

136. The understanding lieth hidden and secret in those words. Could not he

have made all his works in one day? Neither can we properly say there was any

day before the sun was; for in the deep there is but one day [in all].

137. But the understanding lieth hidden in those words. He understandeth by

each day's working, the creation or manifestation of the seven properties; for

he saith, In the beginning God created heaven and earth.

The First Day

138. In the FIRST [1] motion, the magnetical desire compressed and compacted

the fiery and watery Mercury with the other properties; and then the grossness

separated itself from the spiritual nature: and the fiery became metals and

stones, and partly salnitre, that is, earth: and the watery became water. Then

the fiery Mercury of the working became clean, and Moses calleth it heaven; and

the Scripture saith, God dwelleth in heaven: for this fiery Mercury is the

power and virtue of the firmament, viz, an image and resemblance of the

spiritual world, in which God is manifested.

[1] the first day

139. When this was done, God said, Let there be light; then the inward thrust

itself forth through the fiery heaven, from which a shining power and virtue

arose in the fiery Mercury, and that was the light of the outward nature in the

properties, wherein the [1] vegetable life consisteth.

[1] or growing

The Second Day.

140. In the SECOND day's work, God separated the watery and fiery Mercury

from one another, and called the fiery the firmament of Heaven, which came out

of the midst of the waters, viz. of Mercury, whence arose the male and female

[1] kind, in the spirit of the outward world; that is, the male in the fiery

Mercury, and the female in the watery.

[1] or sex

141. This separation was made all over in everything, to the end that the fiery

Mercury should desire and long for the watery, and the watery for the fiery;

that so there might be a desire of love betwixt them in the light of nature,

from which the conjunction ariseth therefore the fiery Mercury, viz, the

outflown word, separated itself according both to the fiery and to the watery

nature of the light, and thence comes both the male and female kind in all

things, both animals and vegetables.

The Third Day.

142. In the THIRD day's work, the fiery and watery Mercury entered again into conjunction or mixture, and embraced one another, wherein the salnitre, viz, the separator in the earth, brought forth grass, plants, and trees; and that was the first generation or production between male and female.

The Fourth Day.

143. [n the FOURTH day's work the fiery Mercury brought forth its fruit,

viz, the fifth essence, a higher power or virtue of life than the four

elements, and yet it is in the elements.: of it the stars are made.

144. For as the compression of the desire brought the earth into a [1] mass,

the compressure entering into itself, so the fiery Mercury thrust itself

outwards by the compressure, and hath enclosed the place of this world with the

[2] stars and starry heaven.

[1] or lump [2] or constellations

The Fifth Day.

145. In the FIFTH day's work the [1] spiritus mundi, that is, the [2] soul

of the great world, opened itself in the fifth essence (we mean the life of the

fiery and watery Mercury); therein God created all beasts, fishes, fowls, and

worms; every one from its peculiar property of the divided Mercury.

[1] spirit of the world [2] amima macrocosmi

146. Here we see how the eternal Principles have moved themselves according to

evil and good, as to all the seven properties, and their effluence and mixture;

for there are evil and good creatures created, everything as the Mercury (that

is, the separator) hath figured and [1] framed himself into an ens, as may be

seen in the evil and good creatures: And yet every kind of life hath its

original in the light of nature, that is, in the love of nature; from which it

is that all creatures, in their kind or property, love one another according to

this outflown love

[1] or imaged .

The Sixth Day.

147. In the SIXTH day's work, God created man; for in the sixth day the

understanding of life opened itself out of the fiery Mercury, that is, out of

the inward ground.

148. God created him in his likeness, out of all the three Principles, and made

him an image, and breathed into him the understanding fiery Mercury, according

to both the inward and outward ground, that is, according to time and eternity,

and so he became a living understanding soul: and in this ground of the soul,

the manifestation of the divine holiness did move, viz. the living outflowing

Word of God, together with * the eternal knowing

idea, which was known from eternity in the divine wisdom, as a subject

or form of the divine imagination.

* "the eternal knowing idea," lit., "the eternally known

idea."

149. This [1] idea becomes [2] clothed with the substance of the heavenly

world, and so it becometh an understanding spirit and temple of God; an image

of the divine [3] vision, which spirit is given to the soul for a spouse: as

fire and light are espoused together, so it is here also to be understood.

[1] or images [2] endued or invested [3] or

contemplation

150. This divine ground budded and pierced through soul and body; and this was

the true paradise in man, which he lost by sin, when the ground of the dark

world, with the false desire, got the upper hand and dominion in him.

The Seventh Day.

151. In the SEVENTH day God rested from all his works which he had made,

saith Moses; yet God needeth no rest, for he hath wrought from eternity, and he

is a mere working power and virtue; therefore the meaning and understanding

here lieth hidden in the word, for Moses saith he hath commanded [us] to rest

on the seventh day.

152. The seventh day was the true paradise (understand it spiritually), that

is, the tincture of the divine power and virtue, which is a temperament; this

pierced through all the properties, and wrought in the seventh, that is, in the

substance of all the other.

153. The tincture pierced through the earth, and through all elements, and

tinctured all; and then paradise was on earth, and in man; for evil was hidden:

as the night is hidden in the day, so the [1] wrath of nature was also hidden

in the first Principle, till the fall of man; and then the divine working, with

the tincture, [2] fled into their own Principle, viz, into the inward ground of

the light-world

[1] or grim fierceness [2] or retired .

154. For the wrath arose aloft, and got the predominancy, and that is the

curse, where it is said, God cursed the earth; for his cursing is to leave off

and fly from his working: as when God's power and virtue in a thing worketh

with the life and spirit of the thing, and afterwards withdraweth itself with

its working; then the thing is cursed, for it worketh in its own will, and not

in God's will.

Of the Spiritus Mundi, and of the Four Elements.

155. We may very well observe and consider the hidden spiritual world by the

visible world: for we see that fire, [1] light, and air, are continually

begotten in the deep of this world; and that there is no rest or cessation from

this begetting; and that it hath been so from the beginning of the world; and

yet men can find no cause of it in the outward world, or tell what the ground

of it should be: but reason saith, God hath so created it, and therefore it

continueth so; which indeed is true in itself; but reason knoweth not the

Creator, which doth thus create without ceasing; that is, the true [2]

Archaeus, or separator, which is an effluence out of the invisible world, viz,

the outflown Word of God; which I mean and understand by the word fiery

Mercury.

[1] or water [2] distinguisher or divider

156. For what the invisible world is, in a spiritual working, where light and

darkness are in one another, and yet the one not comprehending the other, that

the visible world is, in a substantial working; whatsoever powers and virtues

in the outflown word are to be [1] understood in the inward spiritual world,

the same we understand also in the visible world, in the stars and elements,

yet in another Principle of a more holy [2] nature.

[1] or conceived [2] kind, quality, or condition

157. The four elements flow from the Archaeus of the inward ground, that is,

from the four properties of the eternal nature, and were in the beginning of

time so outbreathed from the inward ground, and compressed and formed into a

working substance and life; and therefore the outward world is called a

Principle, and is a subject of the inward world, that is, a tool and instrument

of the inward [1] master, which [1] master is the word and [3] power of

God.

[1] artificer or workman [2] or virtue

158. And as the inward divine world hath in it an [1] understanding life from

the effluence of the divine knowledge, whereby the angels and souls are meant;

so likewise the outward world hath a rational life in it, consisting in the

outflown powers and virtues of the inward world; which outward [rational] life

hath no higher understanding, and can teach no further than that thing wherein

it dwelleth, viz, the stars and four elements.

[1] or intellectual

159. The spiritius mundi is hidden in the four elements, as the soul is in the

body, and is nothing else but an effluence and working power proceeding from

the sun and stars; its dwelling wherein it worketh is spiritual, encompassed

with the four elements.

160. The spiritual house is first a sharp magnetical power and virtue, from the

effluence of the inward world, from the first property of the eternal nature;

this is the ground of all salt and powerful 'virtue, also of all forming and

substantiality.

161. Secondly, it is the effluence of the inward motion, which is outflown from

the second [1] form of the eternal nature, and consisteth in a fiery nature,

like a dry kind of water source, which is understood to be the ground of all

metal and stones, for they were created of that.

[1] species, kind, or property

162. I call it the fiery Mercury in the spirit of this world, for it is the

mover of all things, and the separator of the powers and virtues; a former of

all shapes, a ground of the outward life, as to the motion and sensibility.

163. The third ground is the perception in the motion and sharpness, which is a

spiritual source of Sulfur, proceeding from the ground of the painful will in

the inward ground: Hence the spirit with the five senses ariseth, viz. seeing,

hearing, feeling, tasting, and smelling; and is the true essential life,

whereby the fire, that is, the fourth form, is made manifest.

164. The ancient wise men have called these three properties Sulfur, Mercurius,

and Sal, as to their materials which were produced thereby in the four

elements, into which this spirit doth coagulate, or make itself

substantial.

165. The four elements lie also in this ground, and are nothing different or

several from it; they are only the manifestation of this spiritual ground, and

are as a dwelling place of the spirit, in which this spirit worketh.

166. The earth is the grossest effluence from this subtle spirit; after the

earth the water is the second; after the water the air is the third; and after

the air the fire is the fourth: All these proceed from one only ground, viz,

from the spiritus mundi, which hath its root in the inward world.

167. But reason will say, To what end hath the Creator made this manifestation?

I answer, There is no other cause, but that the spiritual world might thereby

bring itself into a visible form or image, that the inward powers and virtues

might have a form and image: Now that this might be, the spiritual substance

must needs bring itself into a material ground, wherein it may so figure and

form itself; and there must be such a separation, as that this separated being

might continually long for the first ground again, viz, the inward for the

outward, and the outward for the inward.

168. So also the four elements, which are nothing else inwardly but one only

ground, must long one for the other, and desire one another, and seek the

inward ground in one another.

169. For the inward element in them is divided, and the four elements are but

the properties of that divided element, and that causeth the great anxiety and

desire betwixt them; they will continually [to get] into the first ground

again, that is, into that one element in which they may rest; of which the

Scripture speaketh, saying: Every creature groaneth with us, and earnestly

longeth to be delivered from the vanity, which it is subject unto against its

will.

170. In this anxiety and desire, the effluence of the divine power and virtue,

by the working of nature, is together also formed and brought into figures, to

the eternal glory and contemplation of angels and men, and all eternal

creatures; as we may see clearly in all living things, and also in vegetables,

how the divine power and virtue [1] imprinteth and formeth itself

[1] fashioneth

171. For there is not anything substantial in this world, wherein the image,

resemblance, and form of the inward spiritual world doth not stand; whether it

be according to the [1] wrath of the inward ground, or according to the good

virtue; and yet in the most [2] venomous virtue or quality, in the inward

ground, many times there lieth the greatest virtue out of the inward world.

[1] or fierceness [2] or poisonous

172. But where there is a dark life, that is, a dark oil, in a thing, there is

little to be expected from it; for it is the foundation of the wrath, viz. a

false, bad poison, to be utterly rejected.

173. Yet where life consisteth in [1] venom, and hath a light or brightness

shining in the oil, viz. in the fifth essence, therein heaven is manifested in

hell, and a great virtue lieth hidden in it: this is understood by those that

are ours.

[1] or pain

174. The whole visible world is a mere spermatical working ground; every [1]

thing hath an inclination and longing towards another, the uppermost towards

the undermost, and the undermost towards the uppermost, for they are separated

one from the other; and in this hunger they embrace one another in the

desire.

[1] or substance

175. As we may know by the earth, which is so very hungry after the [influence

and virtue of the] stars, and the spiritus mundi, viz. after the spirit from

whence it proceeded in the beginning, that it hath no rest, for hunger; and

this hunger of the earth consumeth bodies, that the spirit may be parted again

from the gross elementary [1] condition, and return into its [2] Archaeus

again.

[1] or property [2] separator, divider, or salnitrous

virtue

176. Also we see in this hunger the impregnation of the Archaeus, that is, of

the separator, how the undermost Archaeus of the earth attracteth the outermost

subtle Archaeus from the constellations above the earth; where this compacted

ground from the uppermost Archaeus longeth for its ground again, and putteth

itself forth towards the uppermost; in which putting forth, the growing of

metals, plants and trees, hath its original.

177. For the Archaeus of the earth becometh thereby exceeding joyful, because

it tasteth and feeleth its first ground in itself again, and in this joy all

things [1] spring out of the earth, and therein also the growing of animals

consisteth, viz. in a continual conjunction of the heavenly and earthly, in

which the divine power and virtue also worketh, as may be known by the tincture

of the vegetables in their inward ground.

[1] or grow

178. Therefore man, who is so noble an image, having his ground in time and

eternity, should well consider himself, and not run headlong in such blindness,

seeking his native country afar off from himself, when it is within himself,

though covered with the grossness of the elements by their strife.

179. Now when the strife of the elements ceaseth, by the death of the gross

body, then the spiritual man will be made manifest, whether he be born in and

to light, or darkness; which of these [two] beareth the sway, and hath the

dominion in him, the spiritual man hath his being in it eternally, whether it

be in the foundation of God's anger, or in his love.

180. For the outward visible man is not now the image of God, it is nothing but

an image of the Archaeus, that is, a house [or husk] of the spiritual man, in

which the spiritual man groweth, as gold doth in the [1] gross stone, and a

plant from the wild earth; as the Scripture saith, [2] As we have a natural

body, so we have also a spiritual body: such as the natural is, such also is

the spiritual.

[1] or drossy [2] 1 Cor 15:44

181. The outward gross body of the four elements shall not inherit the kingdom

of God, but that. which is born out of that one element, viz. out of the divine

manifestation and working.

182. For this body of the flesh and of the will of man is not it, but that

which is wrought by the heavenly Archaeus in this gross body, unto which this

gross [body] is a house, tool, and instrument.

183. But when the crust is taken sway, then it shall appear wherefore we have

here been called men; and yet some of us have scarce been beasts; nay, some far

worse than beasts.

184. For we should rightly consider what the spirit of the outward world is; it

is a house, husk, and instrument of the inward spiritual world which is hidden

therein, and worketh through it, and so bringeth itself into figures and

images.

185. And thus human reason is but a [1] house of the true understanding of the

divine knowledge: none should trust so much in his reason and sharp wit, for it

is but the constellation of the outward stars, and doth rather seduce him, than

lead him to the Unity of God.

[1] or dwelling

186. Reason must wholly yield itself up to God, that the inward Archaeus may be

revealed; and this shall work and bring forth a true spiritual understanding

ground, uniform with God, in which God's spirit will be revealed, and will

bring the understanding to God: and then, in this ground, [1] the spirit

searcheth through all things, even the deep things of [2] God, as St. Paul

saith.

[1] 1 Cor 2:10 [2] or of the Deity

187. I thought good to set this down thus briefly of Mysteries. for the lovers,

[1] for their further consideration.

[1] of Mysteries

Now followeth a short Explication, or [1] Description of the Divine

Manifestation.

[1] formula or model

188. God is the eternal, * immense,

incomprehensible Unity, which manifesteth itself in itself, from eternity in

eternity, by the Trinity; and is Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, in a threefold

working, as is before mentioned.

* "immense" (unmessliche), "immeasurable."

189. The first effluence and manifestation of this Trinity is the eternal Word,

or outspeaking of the divine power and virtue.

190. The first outspoken substance from that power is the divine wisdom; which

is a substance wherein the power worketh.

191. Out of the wisdom floweth the power and virtue of the breathing forth, and

goeth into separability and forming; and therein the divine power is manifest

in its virtue.

192. These separable powers and virtues bring themselves *

into the power of reception, to their own perceptibility; and out of the

perceptibility ariseth own self-will and desire: this own will is the ground of

the eternal nature, and it bringeth itself, with the desire, into the

properties as far as fire.

* "into the power of reception, to their own perceptibility"

(Selbst-Empfindlichkeit), or "into receptibility to

self-perceptibility."

193. In the desire is the original of darkness; and in the fire the eternal

Unity is made manifest with the light, in the fiery nature.

194. Out of this fiery property, and the property of the light, the angels and

souls have their original; which is a divine manifestation.

195. The power and virtue of fire and light is called tincture; and the motion

of this virtue is called the holy and pure element.

196. The darkness becometh substantial in itself; and the light becometh also

substantial in the fiery desire: these two make two Principles, viz. God's

anger in the darkness, and God's love in the light; each of them worketh in

itself, and there is only such a difference between them, as between day and

night, and yet both of them have but one only ground; and the one is always a

cause of the other, and that the other becometh manifest and known in it, as

light from fire.

197. The visible world is the third Principle, that is, the third ground and

beginning: this is outbreathed out of the inward ground, viz. out of both the

first Principles, and brought into the nature and form of a creature.

198. The inward eternal working is hidden in the visible world; and it is in

everything, and through everything, yet not to be comprehended by anything in

the thing's own power; the outward powers and virtues are but passive, and the

house in which the inward work.

199. [1] All the other worldly creatures are but the substance of the outward

world, but man, who is created both out of time and eternity, out of the Being

of all ,beings, and made an image of the divine manifestation.

[1] the common creatures

200. The eternal manifestation of the divine light is called the kingdom of

heaven, and the habitation of the holy angels and souls.

201. The fiery darkness is called hell, or God's anger, wherein the devils

dwell, together with the damned souls.

202. In the place of this world, heaven and hell are present everywhere, but

according to the inward ground.

203. Inwardly, the divine working is manifest in God's children; but in the

wicked, the working of the painful darkness.

204. The place of the eternal paradise is hidden in this world, in the inward

ground; but manifest in the inward man, in which God's power and virtue

worketh.

205. There shall perish of this world only the four elements, together with the

starry heaven, and the earthly creatures, viz. the outward gross life of all

things.

206. The inward power and virtue of every substance remaineth eternally.

Another Exposition of the Mysterium Magnum.

207. God hath manifested the [1] Mysterium Magnum out of the power and

virtue of his Word; in which Mysterium Magnum the whole creation hath lain

essentially without forming, in temperamento; and by which he hath outspoken

the spiritual formings in separability [or variety]: in which formings, the

sciences of the powers and virtues in the desire, that is, in the Fiat, have

stood, wherein every science, in the desire to manifestation, hath brought

itself into a corporeal substance.

[1] The Great Mystery

208. Such a Mysterium Magnum lieth also in man, viz. in the image of God, and

is the essential Word of the power of God, according to time and eternity, by

which the living Word of God out- speaketh, or expresseth. itself, either in

love or anger, or in fancy, all as the Mysterium standeth in a movable desire

to evil or good; according to that saying, Such as the people is, such a God

they also have.

209. For in whatsoever properties the Mysterium in man is awakened, such a word

also uttereth itself from his powers: as we plainly see that nothing else but

vanity is uttered by the wicked. Praise the Lord, all ye his works.

Hallelujah.

Of the Word SCIENCE

[1] or SCIENTZ

210. The word Science is not so taken by me as. men understand the word

scientia in the Latin tongue; for I understand therein even the true ground

according to sense, which, both in the Latin. and all other languages is missed

and neglected by ignorance; for every word in its impressure, forming, and

expression, gives the true understanding of what that thing is that is so

called.

211. You understand by Science some skill or knowledge, in which you say true,

but do not fully express the meaning.

212. Science is the root to the understanding, as to the [1] sensibility; it is

the root to the center of the [2] impressure of nothing into something; as when

the will of the abyss attracteth. itself into itself, to a center of the

impressure, viz. to the word, then ariseth the true understanding.

[1] cogitation, consideration, or reasoning [2] or

forming

213. The will is in the separability of the Science, and there separateth

itself out from the impressed compaction; and men first of all understand the

essence in that which is separated, in which the separability impresseth itself

into a substance.

214. For [1] essence is a substantial power and virtue, but Science is a moving

flitting one, like the senses; it is indeed the root of the senses.

[1] ESSENTZ

215. Yet in the understanding, in which it is called Science, it is not the

sensing, but a cause of the sensing, in that manner as when the understanding

* impresseth itself in the mind, there must first be

a cause which must ** give the mind, from which the

understanding floweth forth into its contemplation: Now this Science is the

root to the fiery mind, and it is in short the root of all spiritual

beginnings; it is the true root of souls, and proceedeth through every life,

for it is the ground from whence life cometh.

* "impresseth itself" (fasset sich), or "concretes

itself."

** "give the mind," or "produce," "give rise to the mind."

216. I could not give it any other better name, this doth so wholly accord and

agree in the sense; for the Science is the cause that the divine abyssal will

compacteth and impresseth itself into nature, to the separable [various],

intelligible, and perceivable life of understanding and difference; for from

the impressure of the Science, whereby the will attracteth it into itself

* the natural life ariseth, and the word of every

life originally.

* "the natural life ariseth," etc., or, "originateth the

natural life, and the word of every life [or all life]."

217. The distinction or separation out of the fire is to be understood as

followeth: The eternal Science in the will of the Father draweth the will,

which is called Father, into itself, and shutteth itself into a center of the

divine generation of the Trinity, and by the Science speaketh itself forth into

a word of understanding; and in the speaking is the separation in the Science;

and in every separation there is the desire to the impressure of the [1]

expression, the impressure is essential, and is called divine essence.

[1] or out-speaking

218. From this essence the word expresseth itself in the second separation,

that is, of nature, and in that expression (wherein the natural will separateth

itself in its center, into a sensing), the separation out of the fiery [1]

Science is understood; for thence cometh the soul and all angelical

spirits.

[1] one copy has essence

219. The third separation is according to the outward nature of the expressed

formed word, wherein the bestial Science lieth, as may be seen in the treatise

of the Election of Grace, which hath a [1] sharp understanding, and is one of

the clearest of our writings.

[1] acute or sublime